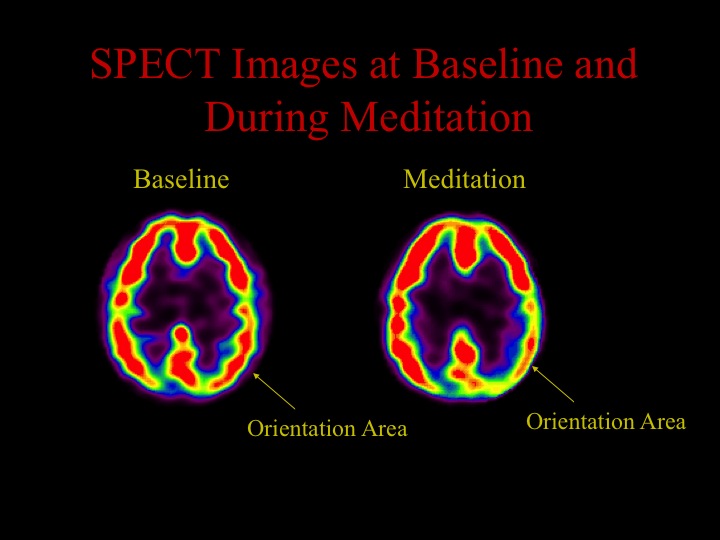

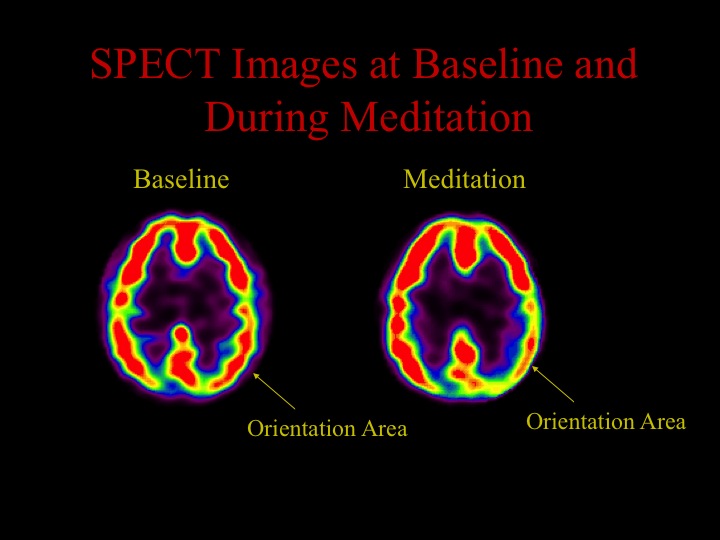

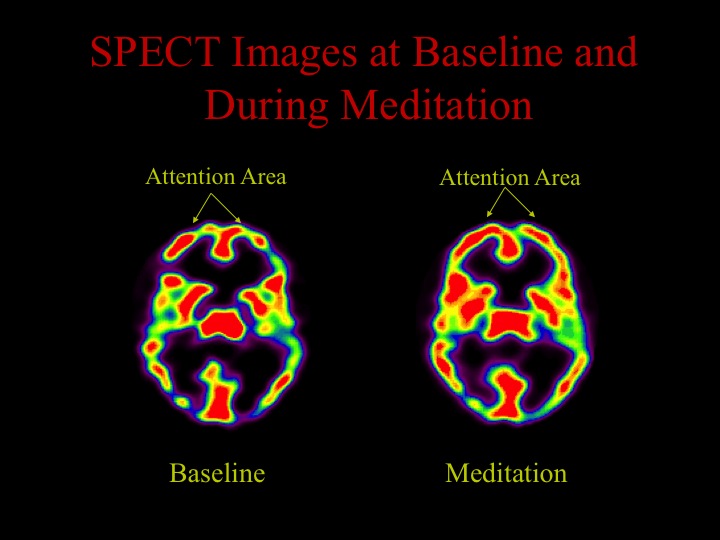

To look at the neurophysiology of religious and spiritual practices, we used a brain imaging technology called single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), which allows us to measure blood flow. The more blood flow a brain area has, the more active it is (red > yellow > green > blue > black). When we scanned the brains of Tibetan Buddhist meditators, we found decreased activity in the parietal lobe during meditation (lower right shows up as yellow rather than the red in the left image). This area of the brain is responsible for giving us a sense of our orientation in space and time. We hypothesize that blocking all sensory and cognitive input into this area during meditation is associated with the sense of no space and no time that is so often described in meditation.

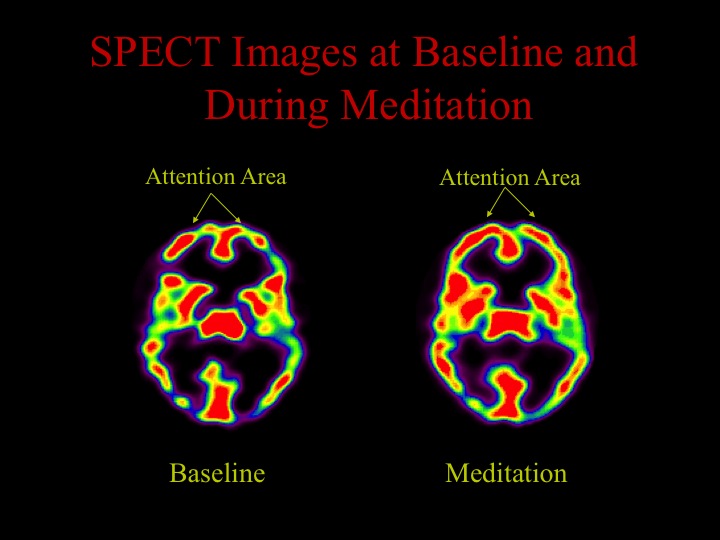

The front part of the brain, which is usually involved in focusing attention and concentration, is more active during meditation (increased red activity). This makes sense since meditation requires a high degree of concentration. We also found that the more activity increased in the frontal lobe, the more activity decreased in the parietal lobe. A more complex version of the model from which the hypothesis is based can be found in my book Why God Won’t Go Away, written with Eugene d’Aquili.

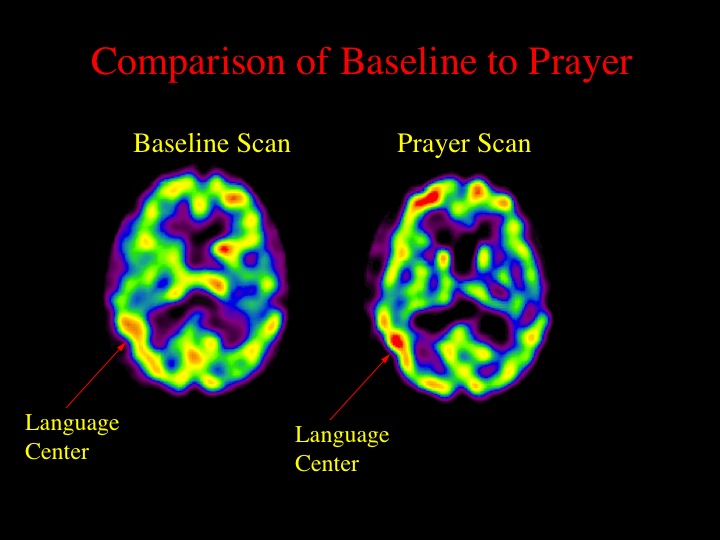

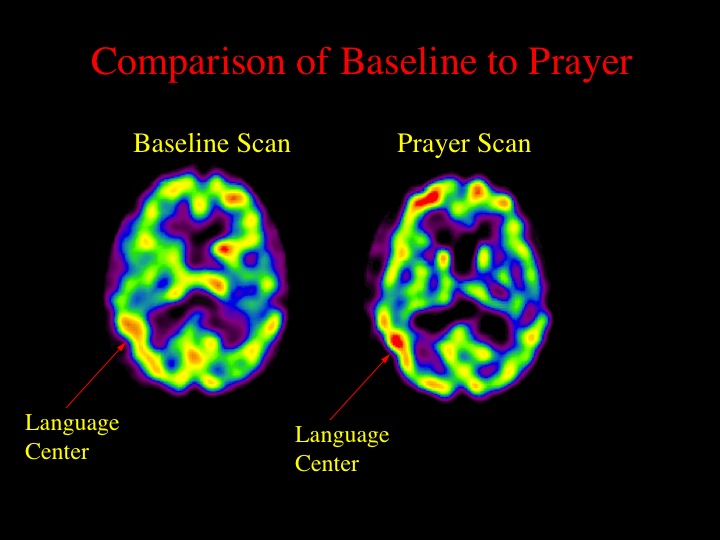

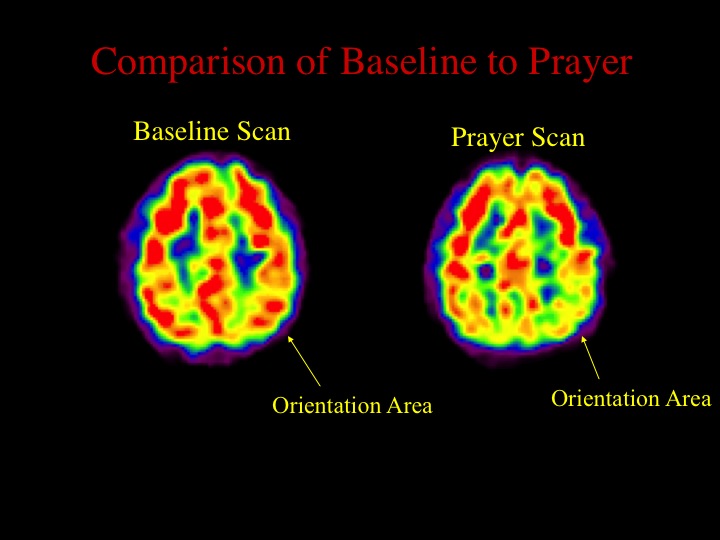

When we looked at the brains of Franciscan nuns in prayer, we found increased activity in the frontal lobes (same as Buddhists), but also increased activity in the inferior parietal lobe (the language area). This latter finding makes sense in relation to the nuns doing a verbally based practice (prayer) rather than visualization (meditation).

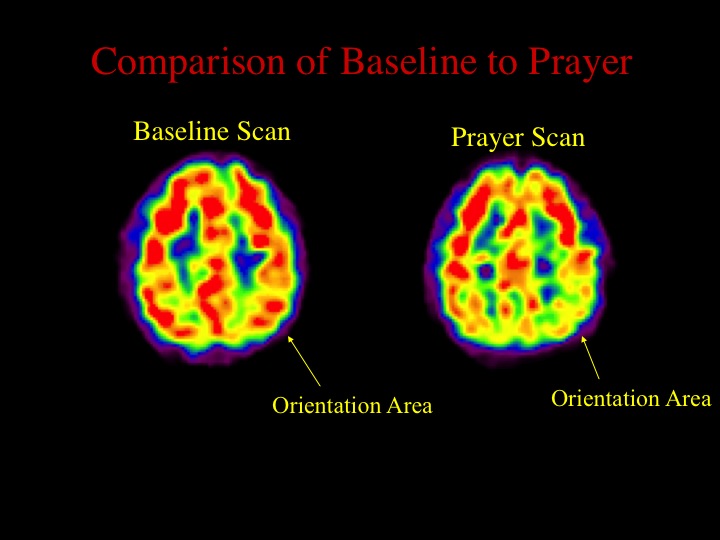

The nuns, like the Buddhists, also showed decreased activity in the orientation area (superior parietal lobes) of the brain. A more thorough description of the results from this study can be found in my book Why We Believe What We Believe, written with Mark Waldman.

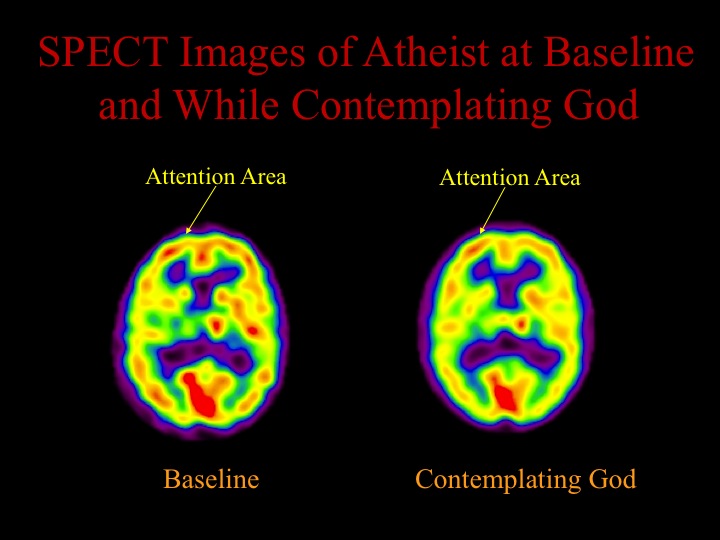

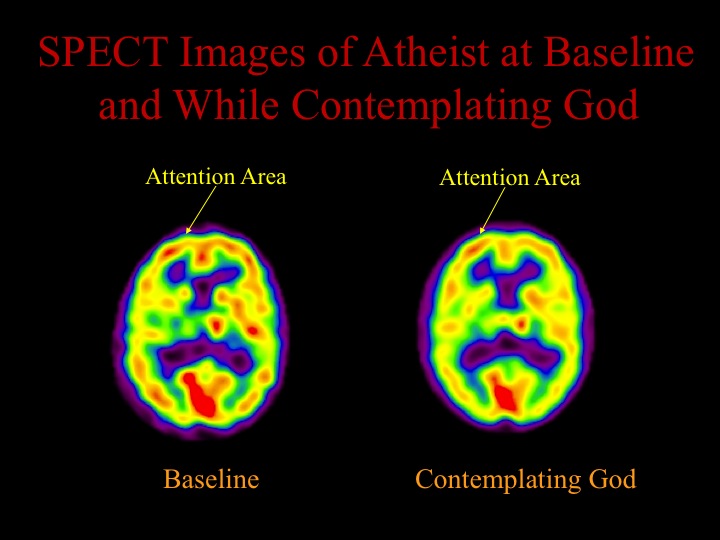

We also looked at the brain of a long-term meditator who was also an atheist. We scanned the person at rest and while meditating on the concept of God. The results showed that there was no significant increase in the frontal lobes as with the other meditation practices. The implication is that the individual was not able to activate the structures usually involved in meditation when he was focusing on a concept that he did not believe in.